News

How Hip Hop Took Over the World, and Quite Possibly Can Save Architecture in the Process

February 1, 2019In the old school days…

If you polled my classmates in 1991, a good many of them may have voted me off the studio. You see, prior to the iPod or iPhone containing a huge library of music; prior to you even having access to a computer in the studio which could also play your music, architecture studios were essentially boom box battle zones. My boom box was among the biggest and hardly anyone else liked my kind of music.

I like a lot of music. Truly. But, for all that is holy, I can only stand so much Brown Eyed Girl or, Lord help me, Best of Billy Joel. Certain people in my studio pirated the airwaves with that junk all day long while professors were mulling around. Either all they had was that one CD or they were too lazy to take it off of “repeat”. It didn’t matter because it was the banal stuff that would offend no one. It was, however, all I could do not to grab their boom box and throw it out the fourth story window onto the unsuspecting engineering students below. During the day, my kind of music was taboo. But as soon as night fell, I pressed ‘play”.

I showed up to college in 1991 with a crate of rap and hip hop cassettes and CD’s. There was no streaming music back then? Remember Columbia House Records? You got 10 CD’s for $1, then you had to buy so many for regular price over then next 37 years. It was a total scam but I had Public Enemy, Ice-T, Big Daddy Kane, Beastie Boys, NWA, Digital Underground, Eric B & Rakim – you get it. I had some punk and what would be called alternative stuff too, but in order to drown out the Chicago Greatest Hits for the eighth time that day, I went to something like Ice Cube. And loud. My friends hated me, but I was 18 and intent on offending those around me whom I had decided had offended me with their oppressively uninspired and stale taste in music all day.

I was nearly alone in my affinity for the genre. They all scoffed at my “Hizzouse” music and they were all sure it (hip hop) would never last as a viable musical category. I did get a few friends together to see Public Enemy, Ice-T and House of Pain at Rec Hall with me in 1992. It was a steal for a $20 ticket! But as Chuck D looked out on us (the audience), I believe he called us “Quaker Land”. Predominately, it was a sea of white kids at Penn State, as it was my studio.

Fast forward almost 30 years. Hip Hop basically took over the world, as we all know. Beyonce, the Kardashians – they all married into hip hop royalty. All of my friends were wrong, and I was obviously right. And today the AIA is literally dying to get some diversity in the profession of architecture. Still. They talked about this 20 years ago.

A couple years ago, a then graduate student in architecture, Michael Ford, blew up the architecture scene with a compelling program called Hip Hop Architecture Camp. From their website:

The Hip Hop Architecture Camp® is a one week intensive experience, designed to introduce under represented youth to architecture, urban planning, creative place making and economic development through the lens of hip hop culture.

Learn more about Hip Hop Architecture Here: HipHopArchitecture.com

Beautiful. How do we get young architects with diverse backgrounds in the pipeline? College is too late. High school is too. Take the message to them early. Make it seem cool and like it can make a difference. Music and architecture have always had this symbiotic relationship. I remember our first year instructor Don going on and on about Mozart’s compositions and how you could have “too many notes” and all that. Did that resonate with 17 and 18 year olds in 1991? Not a bit. Well – maybe a little since I remembered it 27 years later but – Don was no Grandmaster Flash, that’s for sure.

Ford introduces kids to architecture within the context of contemporary messages. Bad environments can produce bad social/economic situations for those who live there. -Of course. Good environments can promote social equity. -There’s the solution based problem solving we need. Architecture is contextual, just as there is a regional component to hip hop. It started as a battle between the Boogie Down Bronx and Queens, but as rap spread, it became East Coast vs. West Coast. Then it became even more regional, so today we have such selections as Dirty South, Crunk, Miami Base; there’s a Chicago scene, a Twin Cities scene, St. Louis, Atlanta…you get the picture. If a certain type of music makes sense in certain place, doesn’t it make sense that maybe the architecture should reflect that too? Ford will personalize his hip hop to the location of the camp.

Hey, it is no coincidence that the rappers I was listening to in the late 80’s / early 90’s are now popular cultural icons with proven acting careers like Ice-T, Ice Cube, LL Cool J, Will Smith, Latifah, Mos Def, Common, etc. The list goes on. These people had something to say, and once our demographic became the one with all the money to spend, producers and sponsors took notice. Now half the commercials on TV have hip hop scores in the background. And by now we’ve all heard that Ice Cube was studying architectural drafting if that whole NWA thing didn’t pan out. Kanye wants to “architect” things. The interests are aligned. Sir Mix A Lot now fronts the Seattle Symphony.

While I may have tried to force my musical preferences on those around me in studio by cranking my box to “11”, it took someone smarter than me to harness the power of hip hop to reach out to youth that maybe wouldn’t have ever considered the career path of architecture or design. If you don’t get what the kids are listening to, they probably know something that you don’t, and maybe never will.

Happy Accidents

November 27, 2018

This is the 45th topic in the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is “Happy Accidents” and was suggested by me this month. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

–>Eric T. Faulkner – Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

When a Mismatch isn a Match — Happy Accident

–>Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

“happy accidents”

–>Nisha Kandiah – The Scribble Space (@KandiahNisha)

Happy Accidents

–>Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

There is no such thing as a happy accident

–>Architalks 45 Anne Lebo – The Treehouse (@anneaganlebo)

Architalks 45 Happy Accidents

Learning from Mistakes

October 1, 2018- Long Lead Items on Short Schedules

- Specific Details on One of a Kind Details

- Demolition Notes

- Existing Conditions

- Door Hardware on Aluminum Storefront

- Utilizing Technical Representatives from Manufacturers

- Specifying Finishes in Publicly Bid Work

Regardless of the size of one’s practice, having a procedure to do a postmortem on even successful jobs is a great way to strive for improvement for your next challenge. While most projects are unique, there are often opportunists to apply what you’ve learned to other situations.

This post is part of the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is “Learning from Mistakes” and was led by Steve Ramos. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

Lee Calisti, AIA – Think Architect (@LeeCalisti)

some kind of mistake

Lora Teagarden – L² Design, LLC (@L2DesignLLC)

Learning from mistakes in architecture

Eric T. Faulkner – Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

Archi-scar – That Will Leave a Mark!

Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

“Learning from Mistakes…”

Brian Paletz – The Emerging Architect (@bpaletz)

Forgotten Mistakes

Jeffrey Pelletier – Board & Vellum (@boardandvellum)

Are Architects Experts?

Keith Palma – Architect’s Trace (@cogitatedesign)

A, B, C, D, E…

Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

Learning from mistakes

Steve Mouzon – The Original Green Blog (@stevemouzon)

How Living Traditions Learn From Mistakes

Designing for Others

September 3, 2018First, I become the Code Official. I am likely seeing this set of documents for the first time. Even if I know a lot about the project, I pretend I do not. The Code Official must be able to review the first several pages of a set and get a general understanding of the existing conditions (if there are any), the type(s) of building(s) proposed, the occupancy, the construction type, the amount of area and height, etc. A lot to do, and it is a challenge to do this clearly and succinctly. Are there fire walls, and if so, where? How much renovation is there (Level 2 or Level 3)? Where are the different uses separated? We have to come up with a way to convey this information even if it means adding little drawing vignettes to clarify.

Next, I try to take the point of view of the people building this structure. How clear are all the transitional details – are there enough blow-ups? Are the required dimensions there? Even if the dimensions are there, are they in the right place, where they make sense to the builder? How have the details considered the person physically putting the drywall on the wall? We also try to incorporate all of the systems and engineering knowledge to coordinate consultant drawings; so that our drawings don’t say one thing, and the electrical drawings say another.There are so many things to consider that, unless you do the same building over and over again, no one would ever catch them all. But we try none-the-less and strive to be better all the time.

This post is part of the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is “Designing for Others” and was led by Jeff Pelletier. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

Jeffrey Pelletier – Board & Vellum (@boardandvellum)

How To Design for Others

Lee Calisti, AIA – Think Architect (@LeeCalisti)

designing for others – how hard could it be?

Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

“designing for others”

Keith Palma – Architect’s Trace (@cogitatedesign)

Just say no

Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

Designing for others

Steve Mouzon – The Original Green Blog (@stevemouzon)

Planting Seeds of Better Design

Anne Lebo – The Treehouse (@anneaganlebo)

Designing for people

Career Path(s)

August 6, 2018I always say I’ve known I wanted to be an architect since the seventh grade, but that doesn’t mean I knew what it meant to be an architect at that time. That didn’t come until much, much later. Even architecture school doesn’t truly prepare one for the path of professional “architect”. It tends to makes sense that, even upon completion of a degree in architecture, many graduates find themselves working outside the field of of architecture eventually (or even immediately).

In my own graduating class of about 25, I estimate that at least one third of said graduates are endeavoring in professions outside of architecture. And of the eight or more “outsiders” I count, gender really has nothing to do with it. And by that I mean: no, it isn’t all the females from our class that dropped out of professional life to raise children. Quite the contrary, actually; as more women from my class are still in architecture and a higher percentage of men have left it.

So where do these people go and why did they leave? Do they do something related to architecture or completely unrelated?

When asked if they intended to seek employment outside of the profession immediately following college, most responded that they first sought traditional work for architectural graduates. Only one intended to pursue work in a related field (architectural preservation). Many found traditional work. Only one person I polled fell into another profession while looking for traditional work; the video gaming industry. In fact when he started in the gaming job, five of the six people on his team were either architecture school graduates or licensed architects.

Only one of the respondents is currently a licensed architect. Having worked for a division of the federal government for several years as their architect, he decided to actually join them as a project manager. As a result, he left the private sector to work for this government agency, running their construction projects as an Owner’s representative.

Another former coworker also got a job with a government agency in a field directly related to architecture. But when it became clear that a transfer from his current city was eminent, he found work in another department in graphics and web design in order to stay put.

My friend Melissa runs a business creating handmade jewelry and other objects made from industrial and recycled materials, see: StubbornStiles. She worked in architectural offices for about ten years before making that move. And if there was anyone I would have expected to do something outside of architecture, it was Mel. Not to say she wasn’t talented and couldn’t have excelled in an office, but I expected her, more than anyone else I knew from college, to create her own professional path. I visited her once in San Francisco many years ago where she was working in a firm, and it was very strange for me to see her step out of the office, dressed the part in every way. What she does now totally fits her. (She was the one with change of major slip at her desk in college). She now works with her super cool and talented family in Portland, Oregon.

My wife worked for a very small architectural firm doing mostly residential work for a short time, but left to work for a nationally known home building company. She liked the residential aspect of the work and she needed to pay off student loans, and this job paid better. She went on to move to where I was living in Lancaster, PA (and we still live there today) and worked for two different regional home builders. She went part time after our first child and eventually quite all together after our second. She never fully intended to leave the work force, and continued to freelance drafting work. Eventually, an opportunity came to her through one of her freelance clients to become what is termed the Transition Specialist for a very large retirement community. She meets with clients who will be moving into the retirement community, measures their furnishings that will be going with them, and lays out the furniture plan for them in their new apartment plan. She also provides tips for selling the home they are leaving.

I know or know of others that have gone into designing and building furniture, culinary and catering endeavors, and even a needlework shop and business. It is clear that all of these changes in profession have one thing in common: there is still an aspect of design and/or art relating to them all. When asked how their architectural education benefited them in their non-traditional professional field, the answer returned was unanimous from the focus group: the ability to problem solve. It is a different kind of problem solving than the engineer or mathematician. The problems presented to architects and even to students in school are open-ended and never only have one answer. We are taught to think in terms of options. The solution that is best for Client A is almost certainly not the best solution for Client B.

The architect must work between what the client thinks they need, what the codes require and what the engineers need to do. I have always thought that being an architect requires, almost above all else, the ability to compromise. The best solutions can answer questions that weren’t even asked. Architecture school teaches creative thinking to spatial problems as well as time management skills. It also teaches how to take criticism. Does it ever…

Most of the people in my limited survey also know others in their fields who studied architecture or were architects. The last couple of decades have seen a few deep recessions. Architecture was one of those majors everyone was warned against very recently, see: Degrees to Avoid. Getting a job in architecture has been difficult at several times over the course of the last 20 years, which can influence some to abandon the traditional route and go into something else. There are also several famous folks who at least started an architectural education before going off to become famous for other things. See: Career Paths. Some actually got their degrees and practiced before going into acting, singing, even royalty…good work if you can find it.

Several respondents suggested they didn’t know what they were getting into. There are a lot of programs today targeting high school students that didn’t exist when I considered a college major. I actually have volunteered for the program at Penn State. See: Career Advice. This would have been extremely helpful to me as a college freshman and would have provided for a good transition from high school to studio. It turns out there are dozens of these programs over the summer from one week to six weeks. See: Summer Programs. I would tend to think that incoming students at least have the opportunity to know what they are getting into.

Most of the people I polled believe that the education of an architect can provide one with a set of skills that is transferable to other undertakings. Of course to be licensed, there is the Architectural Registration Exam to contend with, along with the NCARB internship requirements. But that is a discussion for another time. Architecture school is not for everyone, considering my class barely graduated 25% of the original first year sudents. Even my colleagues who are in fields that have college programs tailored specifically to them (like animation and stage set design) discover aspects of the architectural program that inform their work. Needless to say, a Bachelor of Architecture or Masters of Architecture is the most direct path to becoming a practicing architect. But an architectural course of study is able to translate to a wide variety of career pursuits.

–>Jeff Echols – Architect Of The Internet (@Jeff_Echols)

Well, How Did I Get Here (Again)

–>Lee Calisti, AIA – Think Architect (@LeeCalisti)

a paved but winding career path

–>Eric T. Faulkner – Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

Career – The News Knows

–>Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

#architalks 41 “Career Path”

–>Brian Paletz – The Emerging Architect (@bpaletz)

A Winding Path

–>Drew Paul Bell – Drew Paul Bell (@DrewPaulBell)

Career Path

–>Jeffrey Pelletier – Board & Vellum (@boardandvellum)

Career Path of an Architect (And Beyond)

–>Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

Career Path

–>Steve Mouzon – The Original Green Blog (@stevemouzon)

A Strange Career Path

Words

July 10, 2018How we use words is important. They are one of our inexhaustible resources. But if we don’t use them mindfully, there is no limit to the mischief they can cause.

Speaking of “shall”, writers of building codes also LOVE the word “shall”. In case you were wondering (I know you were), the 2009 IBC, 12th Edition mentions the word “shall” 9,109 times. There’s only 716 pages by the way.

Word choice is key. I am a big believer in using as few words as possible to convey a message, whether it be a note on a drawing, an email to a Client, or a response to a Contractor. I wrote another post on that topic here: Yada Yada World, so I won’t get into it here.

But you have to use the right words. I love my daughter dearly, and I am not making light of her auditory processing disorder, but she said the funniest thing at the dinner table recently. She is very musical and volunteered to play at this year’s high school graduation. When she told us the tune they were to play, I nearly spit out my peas. She told us she was practicing “Pomp and Circumcision” instead of “Pomp and Circumstance”.

So yeah, words are important.

This post is part of the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is “Words” and was led by Jeremiah Russell. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

Jeff Echols – Architect Of The Internet (@Jeff_Echols)

Does anyone hear your words?

Lora Teagarden – L² Design, LLC (@L2DesignLLC)

Visual Words

Eric T. Faulkner – Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

Words are Simple — Too Simple

Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

“words”

Meghana Joshi – IRA Consultants, LLC (@MeghanaIRA)

Architalks 40: Words

Brian Paletz – The Emerging Architect (@bpaletz)

A pictures worth

Drew Paul Bell – Drew Paul Bell (@DrewPaulBell)

Mindset for Endless Motivation and Discipline #Architalks

Jeffrey Pelletier – Board & Vellum (@boardandvellum)

Use Your Words (Even When You Can’t)

Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

Words

Leah Alissa Bayer – The Stoytelling LAB (@leahalissa)

Architects Are Storytellers

ArchiDad

June 16, 2018Having children changes anyone. Hopefully it does, anyway. I know it did change me. My wife and I were married for five years before we had children, which I think we both are glad we did. Getting to know your spouse is quite important. Having that time to work on your relationship before you introduce any rug rats, in our opinion, made it easier later for us.

We do all the mundane, architect-y stuff with our kids. They had their share of building blocks and Legos growing up. We yammer on about cool building details when we see them (and they call us nerds). And our kids have been on more than their fair share of architectural tours. We told the kids we are going to Niagara Falls, which of course we did. What we didn’t tell them is that we would be stopping in Buffalo for a couple days and, oh yeah, Frank Lloyd Wright has a few buildings to check out. We went to the Smokey Mountains and, oh yeah, there’s this house we need to see called Biltmore. Now they know better, that there is at least one architecture tour per vacation. But more so than this kind of stuff, being an architect has a lot of the same challenges to home life as other jobs, and maybe just a few unique challenges.

Having kids made me look at the balance in our lives. Life can’t be 99% work and 1% “the rest”. Before kids, that balance was difficult to strike. Kids can have a grounding effect. There is no getting around the fact that this business means some long hours. So does parenting.

| Sometimes it works out for them. They got to swim in the Montreal Olympic Stadium. |

In my career, I also lost my way in taking care of myself. Over the years, bad eating habits and lack of exercise packed on the weight. Having kids makes you think about sticking around as long as you can for them. Last year, I made a commitment to myself (but also still for the family) to take better care of myself. I started a better eating program and I hold two nights a week sacred for working out. I can be flexible with the days but not with the number of days per week. It has paid off, and after losing over fifty pounds, I essentially look at that as more time of better quality that I can spend with the three people I don’t want to be without.

Cue the sappy Brady Bunch interlude music.

|

| That is one sweet T-Square. |

This post is a special Father’s Day Edition of the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog, who are also dads) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This edition was led by Brian Paletz. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects (and dads) are listed below and are worth checking out:

–>Brian Paletz – The Emerging Architect (@bpaletz)

#Archidad – A modern approach

–>Jeremiah Russell, AIA – ROGUE Architecture (@rogue_architect)

Happy Fathers Day #archidads

–>Eric T. Faulkner – Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

The Dad — The Architect

–>Rusty Long – Rusty Long, Architect (@rustylong)

Life as an Archidad

–>Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

ArchiDad

–>Larry Lucas – Lucas Sustainable, PLLC (@LarryLucasArch)

A Daddy Architects Work Life Blur and My Escape

–>Steve Mouzon – The Original Green Blog (@stevemouzon)

Fathers Day for Architects – The Empty Seat

–>Jared W. Smith – Architect OWL (@ArchitectOWL)

ArchiDad on Father’s Day

Happy Father’s Day everyone!

Experience

June 3, 2018

|

| Photo Credit: U.S. Forestry Serivce |

This post is part of the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is “Experience” and was led by Lora Teagarden. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

Lee Calisti, AIA – Think Architect (@LeeCalisti)

experience comes from experiences

Lora Teagarden – L² Design, LLC (@L2DesignLLC)

Gaining Experience As A Young Architect

Jeremiah Russell, AIA – ROGUE Architecture (@rogue_architect)

knowledge is not experience

Eric T. Faulkner – Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

That’s Experience — A Wise Investment

Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

“experience”

Brian Paletz – The Emerging Architect (@bpaletz)

You need it to get it

Jeffrey Pelletier – Board & Vellum (@boardandvellum)

Channeling Experience: Storytelling in the Spaces We Design

Keith Palma – Architect’s Trace (@cogitatedesign)

The GC Experience

Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

Experience

Leah Alissa Bayer – Stoytelling LAB (@leahalissa)

Four Years In: All Experiences Are Not Created Equal (Nor Should They Be)

Unlikely Inspiration

April 27, 2018

Don’t you hate blogs that start with a tired, old cliche? I know I do.

One of the biggest trends in the last 20 years is trying to get some privacy into shared, or double-occupancy nursing rooms. This makes a lot of sense. Shared rooms are much more economical, as that means building half as many bathrooms as private rooms. But residents, family members, health care staff and even HIPPA, want some privacy for each individual occupant. As square footage is king, any ways to improve privacy in tight spaces are at a premium.

I know nursing homes aren’t “sexy” to architects. But consider this is what we are trying to improve:

|

| Typical “semi-Private” Nursing Bed – Unchanged from 1900 |

Ideally, we would layout a new building to provide layouts that accommodate separate quarters for each resident, along with a common foyer that allowed for entry into the bathroom as well as the corridor. Pretty straight forward, but this was not what most nursing rooms looked like in the early 1990’s. This was a big leap. What’s more, if you’ve ever worked in healthcare, you know that they hate pocket doors. You can’t clean the pockets, yet stuff can get back there, so there is a fear of infection, etc. In our original plans, we used cubical curtains.

| State of the Art Circa 1990-something. “Shared Room” takes the place of “Semi-Private. |

What can we do to improve upon this? Doors are the obvious answer, but how? It turns out, we were able to convince the Health Department that “barn doors” are a hygienic alternative to pockets. With a barn door, we get all the benefits of a pocket door and eliminate all the space a typical swinging door needs. Did I mention that all these doors needed to be 3′-8″ wide to be able to move the beds through them in an emergency? Each room not only has its own space, but each bed has a window. Not the case in the first example: one resident gets proximity to a window, the other gets the bathroom door!

Saving space is particularly important in projects that combine additions that have the nice layout of the Shared Room, but also renovations that try to provide the same privacy in a space that wasn’t designed for it. Below is a sample reconfigured space – the exterior walls and corridor walls did not move:

|

| Here we had two former traditional layouts combined but maintain privacy. |

In the diagram above, barn doors can literally slide behind the dressers. Swinging doors would not have worked at all. The bathroom also uses a barn door. In this instance, we were completely re-configuring the space “inside the box”, but were able to provide similar privacy in the renovated space as in the brand new building.

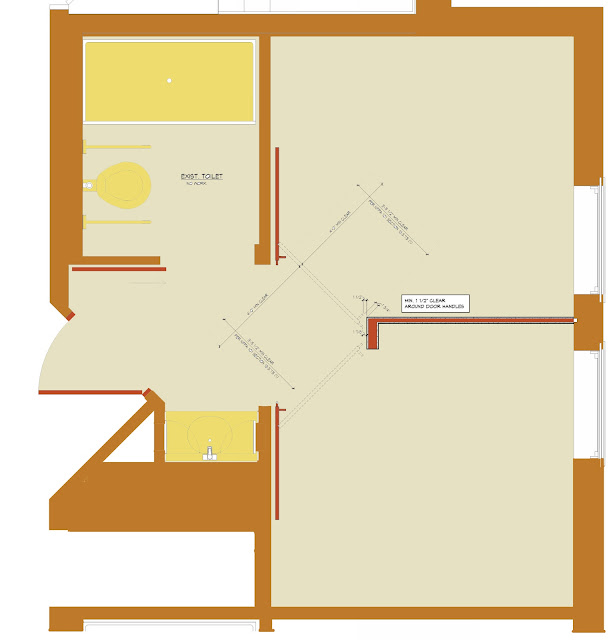

But what if you have a double occupancy room which cannot be reconfigured substantially? The diagram below is an example of that. The alterations only include a dividing wall to create privacy. But the space was so tight, that the openings into the rooms were forced into a 45 degree angle.

|

| Revised room with added privacy wall and sliding doors. |

The intervention is minimal but we are left with a problem as to how to close off the private rooms. The client was not satisfied with cubical curtains. The door track required to open a sliding door at a 45 degree angle is not something that’s off the shelf at Home Depot. As we are not in the business of inventing door hardware, the Contractor and a local metal fabricator designed and built something that actually worked. But that is only the first hurdle. We had to get the health Department to sign off on it. Did I mention that a floor track was forbidden? The Contractor devised a track that ran along the wall to keep the door from flopping around.

A complete mocked up room and opening was built to demonstrate its performance.

| Mock up – Half Open. Or is it Half Closed? |

| Mock up – Mostly Closed. |

| Mock up – Track from Foyer Side. |

| Mock up – Track from Resident Side. |

The door was approved and went on to be installed. Between the modest renovation plans, tight spaces and an Owner who was unwilling to compromise, a brand new type of door was created. We just don’t have a name for it yet. Any inspired suggestions?

|

| Finished project – door in closed position. Transom lights allow borrowed light into the foyer. |

|

| Finished project from the room side. |

This post is part of the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is “Unlikely Inspiration” and was led by Eric Faulkner. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

Lee Calisti, AIA – Think Architect (@LeeCalisti)

unlikely inspiration was there all along

Eric T. Faulkner – Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

Inspire — A Clover

Jeffrey Pelletier – Board & Vellum (@boardandvellum)

Unlikely Inspiration: The Strange Journeys of the Creative Process

Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

Unlikely Inspiration – Herbert Simms

Lora Teagarden – L² Design, LLC (@L2DesignLLC)

Unlikely inspiration

Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

“unlikely inspiration”

Tim Ung – Journey of an Architect (@timothy_ung)

Inspired by Leather Working

Steve Mouzon – The Original Green Blog (@stevemouzon)

A Most Unexpected Inspiration

What Was I Thinking?

April 2, 2018Our office had just completed a very high-profile Seniors apartment that had received lots of awards, had gotten a lot of press in the trades, and was very high end. It had three stories of apartments, each with a nice sized balcony. What more could you ask for, right?

|

| A rendering of the Project. Note some of the balconies are trellises, some have solid roofs. |

One suggestion for the dark balconies was to paint the underside of the roof structure white instead of the dark green of the original design. So instead of getting a painter to paint one of the balconies, an intern architect was dispatched with a knife, a box of white Foam Core sheets, a ruler, a cutting board and several tubes of Liquid Nails. So there I was, in temperature and humidity both in the mid-90’s, on a resident’s balcony. Standing on a ladder, I fitted squares of Foam Core into the coffers of the porch roof while trying to keep the sweat from burning my eyes. I was miserable. Having been part of a meeting prior to this exercise, I had been dressed in a coat and tie, not exactly appropriate for the task at hand.

Not only was the work undesirable, but the gracious gentleman who allowed me to enter his home and walk out on to his balcony had some memory issues. He was also a retired military officer. Though he was extremely accommodating when he first met me, in the time it took me to place the white Foam Core under his roof (I am guessing about two hours), he had kind of forgotten who I was. When I reentered his living room, he didn’t take kindly to me barging into his life and interrupting The Price Is Right. I felt bad, but what could I do? There was no other way off the third floor balcony! I just apologized profusely and left his apartment as quickly as possible.

I am told that the Liquid Nails gave way to the humidity over the summer, dropping the foam panels on the Major’s head every so often. Days like those really made me question my sanity for entering the profession. I am sure the Major would agree with that assessment.

This post is part of the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is “What Was I Thinking” and was led by Cormac Phalen. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

Lora Teagarden – L² Design, LLC (@L2DesignLLC)

What was I thinking?

WWIT — Convenience Kills!

Brian Paletz – The Emerging Architect (@bpaletz)

What was I thinking?

Jeffrey Pelletier – Board & Vellum (@boardandvellum)

What Was I Thinking? (Learning from Your Mistakes When Starting a Business)

Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

What was I thinking!

Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

“what was i thinking?”

Jeremiah Russell, AIA – ROGUE Architecture (@rogue_architect)

what were we thinking: #architalks

Mark R. LePage – EntreArchitect (@EntreArchitect)

What Was I Thinking?

Cormac Phalen – Cormac Phalen (@archy_type)

What was I thinking?