Accessible Doesn’t Mean Institutional

September 3, 2019Many designers and consumers alike have an aversion to anything labeled: accessible. That particular label on an apartment can have a connotation of “institutional” or just plain not looking like all the other residential units. Even in retirement living, the Type A apartments (or so-called “ADA” units), which are required by most building codes to comprise of at least 2% of the total apartment units in a development, are often the hardest to sell. Why? Because they (can) look different. However, with a little creativity and just a couple extra design features, these adaptable units can be almost indistinguishable from the other 98% of the apartments.

To back up a little (warning: building code lesson), all apartments in multi-family living have to meet certain usability requirements. This is a result of the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988, which augmented the original Act of 1968 to extend housing opportunities to those with disabilities. It’s worth noting that this amendment to the Act preceded the Americans with Disabilities Act by two years. The 1988 Fair Housing Act covered all new construction housing after 1991 that connects more than three dwelling units together to meet minimum accessibility requirements. That means that single family homes are exempt, but townhomes, apartments or any other dwellings of four or more connected by any means are regulated, whether rental, simple ownership or condominium. Developers and owners are sometimes unaware of these minimum standards despite the three decades since the law’s implementation.

This means that even the “standard” units in a typical apartment building, typically called Type B, have to meet some minimum standards. These standards include reasonable accommodations to residents even if that may require the resident to modify the unit (at their own cost, mind you, not the landlord’s). The Type A adaptable units, the 2% mentioned above, are scoped out by most building codes. These standards exceed those required even by the Fair Housing Act above, but not to fully accessible criteria as required in, say, a public bathroom.

The main differences between the two types of units lay in the bathrooms and the kitchen. There are other differences, but they probably will not be recognized by the average consumer. Doorways have to be a quarter inch wider, doors need to have certain clearances in front of them and some receptacles and electrical outlets may need to be lower or higher, but only slightly so.

The area dedicated to the bathrooms of the Type A adaptable unit may be larger than the other units, to allow for the five foot turning radius that a wheel chair requires and some of the clear space requirements on the individual fixtures is larger than those required at Type B units. Other than these differences, however, the actual appearance of the adaptable bathroom can be identical to the standard Type B units. The regulations require that in-wall blocking be installed in the bathrooms at the showers and the toilets for the future installation of grab bars and a shower seat. These items do not have to be installed, however, and the blocking is invisible in the finished product. The sink does need to allow a wheel chair to clear the underside, which in many cases eliminates a base cabinet at this location. Even here, the code allows for a removable cabinet, provided it may be removed easily and the flooring and wall finishes continue behind it. A conscientious designer can incorporate a removable sink cabinet that appears to be built in, matching the appearance of any other bathroom in the building. Shower control locations in adaptable units are also required to be on the long wall of the 3’ x 5’ showers typically provided in senior housing. This can place the shower wand in a location that would spray water out of the shower, as opposed to if it were located on one of the short walls. But the code does not prohibit a diverter and a second, fixed head on the short wall, nor does it prohibit a slightly longer hose on the wand and a second holder on the short wall. Either of these solutions, paired with a wand that has an “off” switch on the dial, can overcome this obstacle.

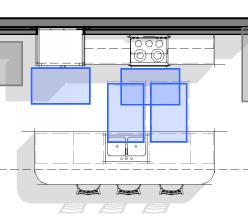

The clear areas dedicated to the kitchen probably is exactly the same between the two types of units, so the Type A kitchen will not necessarily larger than its Type B counterpart. There are, however, two main differences to overcome. First is the provision for a wheel-under sink and a wheel-under work area in the cabinetry. These open cabinets can be filled in exactly as described in the bathroom above. These removable bases can be indistinguishable from those on either side, and removed with just a couple of ordinary screws. The second issue is a little harder to hide. The sink and the work surface have to be a 34” above the floor, which is 2 inches lower than a standard kitchen counter. Typically, the entire kitchen counter is lowered to maintain a consistent countertop height, and while this isn’t required, it does eliminate two low spots on an otherwise regular surface. This is one concession to accessibility that may be difficult to circumnavigate, though in our work in senior living with reputable providers, we have procured variances from the agencies administering the codes to allow traditional 36” countertops provided the building owner promises to replace the entire kitchen counter and necessary cabinets upon the request of a resident. If a variance can be obtained, this essentially eliminates any difference between a Type A and a Type B kitchen.

Designing for accessibility is nothing new, however. Nor should it negatively impact the design. Inform the design – yes: ruin – NO! A real groundswell in advocacy began, with good reason, after World War II. Many thousands of service personnel returned to the US dealing with the physical and mental consequences of modernized warfare. The housing and public facilities to which they returned were not accommodating, and in 1946 a group of paralyzed veterans founded The United Spinal Association in New York; the Paralyzed Veterans of America was founded in 1947; the National Paraplegia Foundation in 1948. Just a few years earlier, accessibility issues were never talked about, not even by our wartime president FDR, who himself used a wheelchair for much of his adult life as a result of contracting polio. But thanks to these service men and women, accessibility advocacy was about to shift to the forefront of public conversation.

Even many architects don’t know that Frank Lloyd Wright, America’s preeminent designer of the first half of the Twentieth Century, designed a house specifically for a client with a physical disability in Rockford, Illinois. In 1949, Wright designed a home for Kenneth Laurent, a disabled veteran, and his wife. The Laurents obtained a $10,000 (that’s about $140,000 today) federal grant for disabled veterans, and Mrs. Laurent wrote to Wright after seeing the Pope-Leighey House in the magazine House Beautiful. She asked Wright if a house could be designed for a wheelchair user on a $20,000 budget. Most of Wright’s Usonian homes are single story and open floor plan affairs. Both of these attributes compliment universal design well.

The Laurent House is consistent with the Wright look and feel, and the incorporated accessible details do not call themselves out. The custom desks, which cantilever from the walls and are completely open below, are as at home here as they would be at Fallingwater, Wright’s famous Pennsylvania home cantilevered off the side of a hill over a waterfall. Even the various storage cabinets fronts were designed to hinge on the bottom instead of the side, making it easier for the client to open them from his wheelchair. The living areas do not express any hint of institutional design. The only perceivable trace at the time may have been wider doors, which to today’s eyes, look completely normal, but in the 40’s it was customary to have 30” bedroom doors rather than a much more wheelchair friendly 36”. Obviously, there are no steps to create barriers into the house from any of the exterior patios, terraces or the carport. Wright’s typical wide overhangs would protect those thresholds from water as well as snow accumulation.

The bathrooms and kitchen were probably the biggest challenge to Wright, as they are to designers today. But it is remarkable that his solutions 70 years ago are strikingly similar to solutions still used today. Let’s be honest. Men of the 1950’s did not likely spend a lot of time in the kitchen. But Wright lowered the countertop to a height similar to the standard required today. To do so, he used a drop in style range so it could be flush with a lower countertop and the controls are all on the front, so that one does not need to reach across the burners and hot pots and pans to adjust the heat. That is an explicit requirement of Type A kitchens today. The kitchen is an open floor plan and allows generous maneuverability within the space. While the kitchen sink is not open below, it is positioned to allow side approach to it. All in all, even with the lower counters, the kitchen looks very much like many other FLW kitchens, and I have visited several.

Wright would have struggled a little with contemporary codes in the bathroom, but nonetheless he came up with a few innovations here worth mentioning. In addition to the traditional bathing tub, Wright added a shower next to it. While it is not a true roll-in shower used today, it has a much shallower curb and would allow for easier transfer to a shower chair than anything readily available in the 1940’s. And while there is not as much clearance at the toilet as you would see today, the lavatory cantilevers from the wall and allows full wheelchair clearance below, which was rather innovative for its time.

The fact that the Laurnets lived in this house for 60 years is a testament to Wright’s foresight into what would one day be called universal design and allowing the family to age in place in their home. They even added on to the house when they adopted a child years later. Perhaps Wright’s age when he first conceived of the home aided his design. He was 82 years old and probably less mobile than he was in his youth.

Accessibility features in living units do not have to constrain design or stand out like billboards. Done sensitively, these features can work seamlessly with the overall design of the space, making it usable to the widest range of potential users possible. It will not just eliminate barriers for those with disabilities, but it should benefit as many users as possible, from those in wheelchairs to those on skateboards.