News

Getting Back to the Office

January 31, 2022It’s good to be back in the office! The return for me was doubly good as I got to move into an office with walls and doors.

You Can’t Take the Code Review out of the Reviewer

My new office door is in close proximity to several of our firm’s designers. Why would that make any difference to the Building Code Compliance person? As I pass everyone’s desk, I look at their drawing boards. Not with any specific intent for code review, but just as a course of curiosity. I will, and do, look at all the projects as they develop: that’s what I am here for. But I previously did not get a chance to look at designs as they are being hatched. When it is early, a lot of creative juices are flowing, and designers can, and should, feel uninhibited to explore any possibility out there. Restrictions of any kind, including building codes, can limit a potential solution. In many cases compliance issues may be addressed in a way that doesn’t compromise that initial (and awesome) solution. But sometimes I just can’t help but feel a disturbance in the Force.

Avoiding a Surfside, Florida Type Disaster

September 16, 2021The following article appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer (with edits) on July 7, 2021.

It seems trite to call the collapse of the Champlain Tower South building in Surfside, Florida tragic, yet that is the closest description I can offer. I cannot pretend to imagine the sorrow and horror experienced by those affected by this event. As the rescue and stabilization efforts continue, it is only natural to wonder – how did this happen? And can it happen here? Don’t we have building codes to prevent something like this?

It is important to note that officials continue to investigate the root cause (or more likely, causes) in this case. I do not intend to speculate on the cause here, but generally speaking, buildings fail due to a compromised skeleton, or structure. Issues can come from sources that aren’t readily observable on the surface. The cause can be from outward forces, such as wind, snow, heat or soil settlement. Faulty water shedding or improper maintenance can also cause corrosion of structural members over time. One may only look to the Grand Canyon to see what water and time can create. Certainly, we can immediately eliminate some of the potential culprits above, but Florida officials and inspectors will likely need months to come to conclusions on Champlain Tower South.

The Pandemic.

February 26, 2021It’s been a while since I’ve dropped a post, hasn’t it? To be honest, it’s been hard to find the motivation to write. To be sure, I’ve been lucky during this pandemic. Our firm’s shift to work from home has been nothing short of seamless. Aside from setting up a temporary work area, to a then in essence a permanent work area (once realization set in that this was not a short-term event), my professional life has been very stable throughout this time.

But life had still become very different. But different doesn’t always mean bad. I thought I would take stock of the things that have been positive about work-from-home in a pandemic.

Accept the Exception

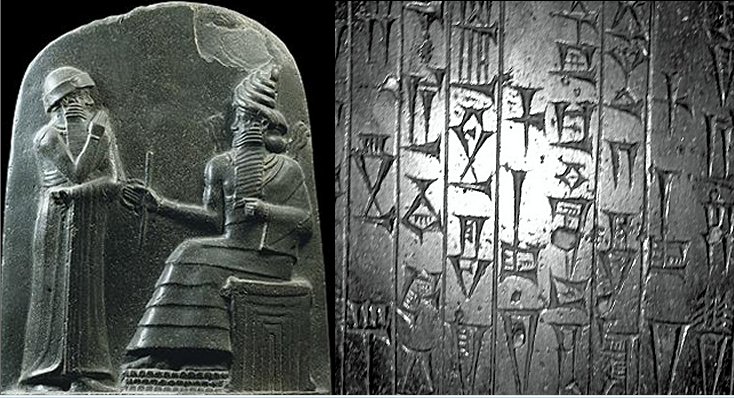

July 2, 2020The earliest known codes that dealt with construction are found within the Code of Hammurabi, which dates back about 1700 years B.C. in Babylon. Since building codes deal with permanent structures that are figuratively and sometimes literally concrete, some may be surprised that today’s codes are not so absolute and clear-cut as say, a rental agreement on an apartment. In the case of old King Hammurabi, it was very definitive – should a house fall down on its owner, the builder shall be put to death! Today (thankfully) construction law is not so strictly interpreted. This may be because the industry is ever changing in terms of technology and building standards. Or it may be because there are an infinite set of conditions that may be encountered within a design that has not commonly been experienced before. Or it could be a set of existing conditions that is unique to the circumstances of a particular building project. Likely it is some combination of issues.

No matter the reasons, building codes today have a little flex to them. Actually, they have a lot of flex. In the 2015 International Building Code (the one we use in Pennsylvania at the time of this writing), the word “exception” occurs 838 times. The root word “except” without the -ion occurs another 227 times. That is astounding to consider (well, to someone like me it is, anyway).

The reason: normally, the building codes read a little like the Code of Hammurabi:

“You shall do this.”

But in over one thousand instances, you do not have to do “this”, if you do “that, and maybe another thing.” For instance, the Code says that we can only build this type of building so high…except we can go one more story if we sprinkler the building. The Code also says all spaces must have two exits…except for when the room is this small. It goes on and on like this. Exceptions are pervasive in a book that is only 729 pages long, including the cover, preface and table of contents. On average, there are about three exceptions on any two pages staring up at you. And this is just the commercial building code. There are additional codes for energy conservation, plumbing, mechanical, fuel gas and one for just existing buildings and one and two family homes, for which I have not done similar word counts.

But in all seriousness, it makes sense. In my fist example, a sprinklered building is statistically much safer than one that is not. Therefore, if provided with an automatic sprinkler system, buildings can generally be just as safe when little taller and larger than those which are not sprinklered. And, in general, it is a good idea to have two ways out of any space, but is that really necessary in a 10′ x 10′ office? No, of course that would be highly inefficient.

This is why I often need a lot more info when asked a “simple” question by one of my colleagues. This isn’t because I’m nosy, but because the answer can be drastically different if I don’t know, say, the building contains a basement or it is connected to another building into which we count on exiting. Or maybe the building contains a warehouse for fireworks and match sticks under a commercial kitchen with open flames. That last example contains obvious hyperboles, but they illustrate the point that some circumstance are far more hazardous than others, and the Codes account for that.

I am not saying building codes are as complex as corporate tax codes… but they kind of are. Although I am pretty sure I could not convince a building official that a new NFL stadium needs zero bathrooms; where a sly accountant can probably figure out how to pay zero taxes on that same stadium for the next thirty years…so maybe not.

Choose Your Own Code Adventure

May 1, 2020“Nothing pleases me more than to tell you I was wrong.”

When was the last time anyone’s told you that? That was me. The words even surprised me as they rolled off my tongue. As most readers may know, I coordinate many of the code compliance aspects of the firm. I see it as my job to take the most conservative approach to any problem, unless I am told otherwise by those who have the authority to approve a more liberal approach. For that part of the practice, this tactic makes the most sense to me. That way, we do not make assumptions or promises that are not based in 100% reality.

This past week, I have had the opportunity to tell two different Clients that my initial interpretations were more conservative than necessary. I know what you’re thinking. “What’s wrong with this guy, won’t he ever learn?” I tell you what: I would not have changed a thing in my process. “Gee, is this guy stubborn, or what?” Yes, but that isn’t the reason. Please consider the following:

- Building Codes leave a lot of room for interpretation of the local authorities having jurisdiction. The code book even says as much in Chapter 1. In the first instance where I was “wrong”, we were looking to make a similar argument that has worked quite often in certain areas but did not work at all in another location fairly close to this particular project. It would have been unwise to assume the argument would work.

- Codes are a lot like those Choose Your Own Adventure books I used to read when I was a kid. Do you remember those books? At various junctures, the reader is forced to make a choice in the action. Based on that decision, the reader is directed to a different chapter, providing multiple endings in the storyline. In the second instance where I was “wrong” this week, based on choices made, I was able to choose a different outcome. The choice I made required some rather significant rework to an existing building, but once completed, multiple opportunities present themselves. The Client then gets to choose their own adventure and change the outcome of the story. To the Client, the effort was worth it in the end.

- I am built this way. I would rather prepare for the worst and hope for the best any day of the week. And if we are being honest, I would rather call you and tell you I was wrong for being too conservative than to tell you, “Hold everything, we have to undo all those decisions we made based on the loose assumptions!” I mean, in that second call, you’re thinking I am kind of a jerk, right? That first call is so much more pleasant for the both of us.

By now, you’ve probably guessed that when I read those Choose Your Own Adventure books when I was younger, I always chose the “safe” route. You’d be right. But just like real life, those writers always were sure to insert some twists that even the “safe” route caused turmoil and affected the outcome, and the submarine still hits the rocks and sinks to the murky depths of the sea. Thankfully, the writers of code books aren’t so tricky – usually.

Architecture Professors Have No Hearts (Even on Valentine’s Day)

February 11, 2020Life as a college student in the late twentieth century could leave you a little disconnected from society. See, most people didn’t have cell phones, the internet was essentially in its infancy, and heck, we didn’t even have cable TV most of the time I was in college. Maybe someone could pick up the local radio station, but mostly people’s boom boxes blasted competing musical genres from CD’s. Life as an architecture student was even more isolated. I would go days without seeing my roommates, as we spent most of our time in studio. We actually drew on paper and had to do that outside of our 8 foot by 8 foot dorm rooms.

Our kind (architecture students) would miss entire world events sequestered away at our drafting tables. I remember, or rather fail to remember, the following events:

The October 1993 deaths of 18 US soldiers in Somalia

The February 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center

The November 1994 death of Tupac

The April 1995 Bombing of the Federal Building in Oklahoma City

You’d think there was no good news in the early 90’s. But it seems that nearly all of these times corresponded with a massive design critique in architecture school. World events were of secondary concern.

The same was true of holidays. In 1996, I should have had my first Valentine’s Day with the woman who is now my wife. Nay Nay. Turns out, our professors decided that we should spend the holiday with them working on our thesis for the last major critique prior to completion. Lucky for me, my girlfriend was in architecture too. Convenient, right? So we decided to celebrate the day after Valentine’s Day.

In somewhat related circumstances, after 10 semesters worth of tuition, we decided to limit our gifts to each other to ten dollars. After some well-deserved sleep, and an overdue shower and shave, I went over to my girlfriend’s apartment. Most everyone else who celebrated the holiday had already done so by this time, but I had a small bundle of goodies to share with my honey. When I say bundle, I mean a plastic bag from the convenience store I stopped at on the way over. Romantic, huh? Go ahead, you jump to your conclusion and see how you feel in the next paragraph…

When we met up, we each held our “gifts” behind our backs. On the count of three, we exchanged them like hostages. I reached into the bag I received and found nearly identical chocolate treats to those I had purchased. We looked at each other, laughed, and realized that we both bought candy the day after Valentine’s Day at a heavily discounted price! That makes the chocolate even sweeter to me, and I might add that my wife regularly looks for day-after-the-holiday goodies to this day. Continuing on to the card, we each had added a scratch off lottery ticket to the other’s envelope.

In the end, love overcomes all, including mean old architecture professors. Consequently, my wife and I continue to limit our Valentine’s Day spending to $20 (we adjusted for inflation).

Wash Those Dirty Hands!

November 11, 2019I was lucky enough to attend the Twenty-Third Annual Westford Symposium on Building Science – also known as Summer Camp. It was a truly informative experience and, as the title suggests, it touched on many subjects relating to building science. Plus there is a really great barbecue and picnic at the organizer’s home. But is wasn’t all about R-values and air leakage, though. While the symposium covered many topics I expected; like humidity, air-tightness and unvented roofs, it also touched on several other topics that were unexpected (to me anyway).

The one session that maybe struck me with that “duh, why didn’t I think of that” moment, was called, “Architectural Compactness and Hot Water Systems: Good Design Lowers Cost”. Now, I know what you’re thinking – with a title like this, how could you go wrong? But here’s the thing: I’ve thought about this session every time I touch a sink faucet since.

Whether in public buildings, apartments or houses: the faucet is usually really far away from the hot water source. Your second floor bathroom can be on the far side of the house and the hot water heater is located in the garage or mechanical closet, or even the basement. Even if the hot water source happens to be on the same floor as the faucet, the pipes have to run up in to the floor or ceiling, then run horizontally to the wet wall, then up or down again, before it sees daylight. Prior to any hot water reaching your hands, that pipe has to clear a huge volume of cold water that is already in the trunk and branches.

In the study done by the presenter, it found that 80 to 90 percent of the water draws in a typical residence were from the faucet, so let’s concentrate on that for a moment. In the 1980’s the typical faucet in a home used 3.5 gpm (gallons per minute). Today, the worst you can do by code is 2.2 gpm and most efficient faucets are closer to 1.2 gpm. So even though faucet efficiency has improved drastically since the 1980’s (about 66%), we are still wasting a lot of energy down the drain. We are just waiting for it to get hot!

Everybody washes their hands, right? Well, they should, anyway. The CDC (Center for Disease Control) says you have to wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. For the record, the CDC recommends singing the “Happy Birthday” song from beginning to end twice. I wish I had known that earlier, because anyone with kids has probably heard their kids turn on the water long enough to only get through “Happy Birthday to y….” & done. But I digress…

While much of the session was focused on how to keep the “wet” rooms closer to the source. Clearly, we designers can and should learn to do better. But the clearest takeaway for me was this: we wash our hands a lot. Our faucets are usually a single lever, as they are accessible, convenient and easier to change the temperature. If our levers are positions in the “neutral” position (half hot, half cold), and we turn it on 60-100 times a day and run it to wash our hands, we are wasting a lot of hot water!

If we run our faucet for the recommended 20 seconds (minimum, I hope), there is almost no way in most houses (or offices or public restrooms for that matter) that the water will be hot by the time we are done washing our hands. The water already in the pipe is unheated. I know in my house it can take a minute or more for hot water to reach my second story bathroom faucet. An eternity.

But if my faucet is drawing hot water as well as cold when washing my hands, I’ve wasted a lot of energy to heat water that will never touch my hands. By the time the next person touches that faucet, the water I heated in the pipe line will have cooled off because the copper in most houses is not insulated. By simply turning the faucet lever all the way to the right, I use only cold water to wash my hands. No energy wasted.

I came home from Summer Camp all excited about this revelation. There is an obstacle. People (the people I know, anyway) don’t like it when the faucet lever isn’t lined up and nice and straight. My wife, for one, was not impressed. There is a compromise now! In addition to the water efficient faucet, I am told that faucets that will only draw cold water when the lever is straight up and down unless you push it to the left while the water is on are on their way to the market. That way you can leave the lever nice and straight, and not waste that energy.

By the way, the CDC doesn’t care if the water is hot or cold, so unless you have a medical condition, why not use cold?

Accessible Doesn’t Mean Institutional

September 3, 2019Many designers and consumers alike have an aversion to anything labeled: accessible. That particular label on an apartment can have a connotation of “institutional” or just plain not looking like all the other residential units. Even in retirement living, the Type A apartments (or so-called “ADA” units), which are required by most building codes to comprise of at least 2% of the total apartment units in a development, are often the hardest to sell. Why? Because they (can) look different. However, with a little creativity and just a couple extra design features, these adaptable units can be almost indistinguishable from the other 98% of the apartments.

To back up a little (warning: building code lesson), all apartments in multi-family living have to meet certain usability requirements. This is a result of the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988, which augmented the original Act of 1968 to extend housing opportunities to those with disabilities. It’s worth noting that this amendment to the Act preceded the Americans with Disabilities Act by two years. The 1988 Fair Housing Act covered all new construction housing after 1991 that connects more than three dwelling units together to meet minimum accessibility requirements. That means that single family homes are exempt, but townhomes, apartments or any other dwellings of four or more connected by any means are regulated, whether rental, simple ownership or condominium. Developers and owners are sometimes unaware of these minimum standards despite the three decades since the law’s implementation.

This means that even the “standard” units in a typical apartment building, typically called Type B, have to meet some minimum standards. These standards include reasonable accommodations to residents even if that may require the resident to modify the unit (at their own cost, mind you, not the landlord’s). The Type A adaptable units, the 2% mentioned above, are scoped out by most building codes. These standards exceed those required even by the Fair Housing Act above, but not to fully accessible criteria as required in, say, a public bathroom.

The main differences between the two types of units lay in the bathrooms and the kitchen. There are other differences, but they probably will not be recognized by the average consumer. Doorways have to be a quarter inch wider, doors need to have certain clearances in front of them and some receptacles and electrical outlets may need to be lower or higher, but only slightly so.

The area dedicated to the bathrooms of the Type A adaptable unit may be larger than the other units, to allow for the five foot turning radius that a wheel chair requires and some of the clear space requirements on the individual fixtures is larger than those required at Type B units. Other than these differences, however, the actual appearance of the adaptable bathroom can be identical to the standard Type B units. The regulations require that in-wall blocking be installed in the bathrooms at the showers and the toilets for the future installation of grab bars and a shower seat. These items do not have to be installed, however, and the blocking is invisible in the finished product. The sink does need to allow a wheel chair to clear the underside, which in many cases eliminates a base cabinet at this location. Even here, the code allows for a removable cabinet, provided it may be removed easily and the flooring and wall finishes continue behind it. A conscientious designer can incorporate a removable sink cabinet that appears to be built in, matching the appearance of any other bathroom in the building. Shower control locations in adaptable units are also required to be on the long wall of the 3’ x 5’ showers typically provided in senior housing. This can place the shower wand in a location that would spray water out of the shower, as opposed to if it were located on one of the short walls. But the code does not prohibit a diverter and a second, fixed head on the short wall, nor does it prohibit a slightly longer hose on the wand and a second holder on the short wall. Either of these solutions, paired with a wand that has an “off” switch on the dial, can overcome this obstacle.

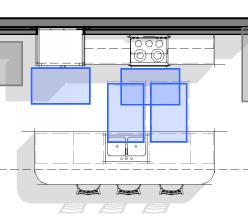

The clear areas dedicated to the kitchen probably is exactly the same between the two types of units, so the Type A kitchen will not necessarily larger than its Type B counterpart. There are, however, two main differences to overcome. First is the provision for a wheel-under sink and a wheel-under work area in the cabinetry. These open cabinets can be filled in exactly as described in the bathroom above. These removable bases can be indistinguishable from those on either side, and removed with just a couple of ordinary screws. The second issue is a little harder to hide. The sink and the work surface have to be a 34” above the floor, which is 2 inches lower than a standard kitchen counter. Typically, the entire kitchen counter is lowered to maintain a consistent countertop height, and while this isn’t required, it does eliminate two low spots on an otherwise regular surface. This is one concession to accessibility that may be difficult to circumnavigate, though in our work in senior living with reputable providers, we have procured variances from the agencies administering the codes to allow traditional 36” countertops provided the building owner promises to replace the entire kitchen counter and necessary cabinets upon the request of a resident. If a variance can be obtained, this essentially eliminates any difference between a Type A and a Type B kitchen.

Designing for accessibility is nothing new, however. Nor should it negatively impact the design. Inform the design – yes: ruin – NO! A real groundswell in advocacy began, with good reason, after World War II. Many thousands of service personnel returned to the US dealing with the physical and mental consequences of modernized warfare. The housing and public facilities to which they returned were not accommodating, and in 1946 a group of paralyzed veterans founded The United Spinal Association in New York; the Paralyzed Veterans of America was founded in 1947; the National Paraplegia Foundation in 1948. Just a few years earlier, accessibility issues were never talked about, not even by our wartime president FDR, who himself used a wheelchair for much of his adult life as a result of contracting polio. But thanks to these service men and women, accessibility advocacy was about to shift to the forefront of public conversation.

Even many architects don’t know that Frank Lloyd Wright, America’s preeminent designer of the first half of the Twentieth Century, designed a house specifically for a client with a physical disability in Rockford, Illinois. In 1949, Wright designed a home for Kenneth Laurent, a disabled veteran, and his wife. The Laurents obtained a $10,000 (that’s about $140,000 today) federal grant for disabled veterans, and Mrs. Laurent wrote to Wright after seeing the Pope-Leighey House in the magazine House Beautiful. She asked Wright if a house could be designed for a wheelchair user on a $20,000 budget. Most of Wright’s Usonian homes are single story and open floor plan affairs. Both of these attributes compliment universal design well.

The Laurent House is consistent with the Wright look and feel, and the incorporated accessible details do not call themselves out. The custom desks, which cantilever from the walls and are completely open below, are as at home here as they would be at Fallingwater, Wright’s famous Pennsylvania home cantilevered off the side of a hill over a waterfall. Even the various storage cabinets fronts were designed to hinge on the bottom instead of the side, making it easier for the client to open them from his wheelchair. The living areas do not express any hint of institutional design. The only perceivable trace at the time may have been wider doors, which to today’s eyes, look completely normal, but in the 40’s it was customary to have 30” bedroom doors rather than a much more wheelchair friendly 36”. Obviously, there are no steps to create barriers into the house from any of the exterior patios, terraces or the carport. Wright’s typical wide overhangs would protect those thresholds from water as well as snow accumulation.

The bathrooms and kitchen were probably the biggest challenge to Wright, as they are to designers today. But it is remarkable that his solutions 70 years ago are strikingly similar to solutions still used today. Let’s be honest. Men of the 1950’s did not likely spend a lot of time in the kitchen. But Wright lowered the countertop to a height similar to the standard required today. To do so, he used a drop in style range so it could be flush with a lower countertop and the controls are all on the front, so that one does not need to reach across the burners and hot pots and pans to adjust the heat. That is an explicit requirement of Type A kitchens today. The kitchen is an open floor plan and allows generous maneuverability within the space. While the kitchen sink is not open below, it is positioned to allow side approach to it. All in all, even with the lower counters, the kitchen looks very much like many other FLW kitchens, and I have visited several.

Wright would have struggled a little with contemporary codes in the bathroom, but nonetheless he came up with a few innovations here worth mentioning. In addition to the traditional bathing tub, Wright added a shower next to it. While it is not a true roll-in shower used today, it has a much shallower curb and would allow for easier transfer to a shower chair than anything readily available in the 1940’s. And while there is not as much clearance at the toilet as you would see today, the lavatory cantilevers from the wall and allows full wheelchair clearance below, which was rather innovative for its time.

The fact that the Laurnets lived in this house for 60 years is a testament to Wright’s foresight into what would one day be called universal design and allowing the family to age in place in their home. They even added on to the house when they adopted a child years later. Perhaps Wright’s age when he first conceived of the home aided his design. He was 82 years old and probably less mobile than he was in his youth.

Accessibility features in living units do not have to constrain design or stand out like billboards. Done sensitively, these features can work seamlessly with the overall design of the space, making it usable to the widest range of potential users possible. It will not just eliminate barriers for those with disabilities, but it should benefit as many users as possible, from those in wheelchairs to those on skateboards.

This Old Architect

July 21, 2019Surprisingly, many of the lessons I’ve learned over the years have little to nothing to do with designing buildings. That doesn’t mean they weren’t worth learning.

Recently, my wife and I were fortunate enough to visit the set of This Old House, which is to say, the active work site of a home renovation in Westerly, Rhode Island. I won a contest as a member of what they call the “Insiders”. It’s a yearly subscription where you get access to every show produced, plus a digital version of the magazine, plus New Yankee Workshop. This is not a commercial but seriously, if you are fan, check it out.

I was extraordinarily excited to put it mildly. My daughter heard me talking about the upcoming trip and hit me with the “Nerd” label. Whatever…! I was stoked. I watched the show as far back as I can remember. You watched what was on then and there were only 12 channels to choose from back in those days, but as my studies and career led toward architecture, I continued to watch. Even with the flood of home improvement shows of the last couple of decades that concentrate on the entertainment rather than the education aspect; or the shock value rather than the shop value, This Old House was always my go to program.

My wife and I watch every Saturday morning with our coffee, whenever possible. We watched together before we even owned a home. In fact, she will be the first to tell you that it was because we would watch this program together and then launch right into a Penn State football game on a Saturday morning, that it first occurred to me to ask her to marry me. Well…It didn’t hurt.

The trip from Southeast PA to Rhode Island was not going to be an easy one, we knew. It is about 300 miles but can take anywhere between 5 and 6 1/2 hours, depending on traffic in the greater New York area. We had to brave it in a torrential down pour, too. We left the night before the shoot in order to be on site by 11 AM on a weekday. We got to our hotel at about 11 PM. The following morning, our hotel room electronic lock decided to malfunction while we went to breakfast. I think I may have scared the young lady working the desk at our hotel after her efforts to open the door went nowhere after about 40 minutes. I believe I demanded a locksmith, another room to shower in, and threatened to tear to the door off the hinges in order to get to the show.

Eventually, the door opened, but we were warned not to shut the door unless someone was inside to reopen it. We only had a short 15 minute drive to the job site. We even had a couple of minutes to spare and drove around the neighborhood and to the shoreline, which was only a mile or so away. Unfortunately, the rain the night before had flooded the shoreline streets, so we had to turn back.

The project house sat at the back of a cul-de-sac bristling with activity. We parked a little way away to keep out of the hustle and bustle of the various work trucks. Other cars started showing up and looking for a place to park like we did. After a while, everyone started migrating over to a pop up tent that looked to be our welcome center. A young man with a huge smile stood at the entrance into the cul-de-sac to greet us – his name was De’Shaun Burnett and we came to learn he was one of the newest apprentices along with Kathryn Fulton. They were so engaging and happy to see all of us, that by the time we had to leave the site, I wanted to adopt them!

As the other winners of the contest assembled, we found that there were about 15 winners and 15 guests coming. Most of the visitors were husband and wife and most of the winners looked to be retirees. So my wife and I pulled the age demographic down – I think there were 3 couples in our age range (40’s) and one couple in their 20’s, but the rest seemed to be in their 60’s. Then I saw the host, Kevin O’Connor walking around the site! I resisted the urge to point and shout, but his presence was definitely noticed by all the other visitors too.

It was an active job site indeed. My wife was in the residential home building industry for a decade, and she commented that she missed the smell of fresh sawn lumber – there was definitely real work being done. At the appropriate time, all of the guests were ushered into a second floor bedroom to watch a very small monitor of the opening shot for the day. There were about 30 folding chairs facing a screen about 24 inches wide. It was kind of funny and Chris Wolfe, who is the Executive Producer and General Manager of all the This Old House Productions television series, made light of the fact that they pulled out all the stops for our visit. It was Chris’ job to entertain us all until the production team was ready downstairs. The group was very engaged and asked a lot of questions, and Chris was reprimanded on one occasion for making us laugh too loud. Questions mainly pertained to the process of how they pick the project houses, at what stage is the design in when they do, how long the process is, etc. The Q&A session could be a long post in and of itself.

The house was essentially fully framed but drywall had not yet started, so from where we sat, we could see the entire floor through the open studs. Obviously any noise would travel down the open stairs to where the team was shooting. They started with the “long open” shot, where Kevin O’Connor arrives on site and walks through the house and happens upon whatever work is happening that day. This day happened to be installing a coffered ceiling detail. We learned later that it was supposed to be installing some doors, but the rainy weather required the team to reorganize the day at the last minute. We obviously had to hush during camera rolling, then between takes, Chris would described various facets of production. During the long shot shooting, we learned that there really is no script, just an outline. Kevin will assess the progress on the house since the last day of shooting and talk with the show runner and crew about what he might say. I think the long shot took about 3 takes and each time Kevin would edit himself and make the shot smoother.

Once he got to the work area inside the house at the end of the long shot, Tommy and Jeff were positioned to talk about the mock-up of the wood trim detail that would become the coffer on the ceiling. It too started with an initial conversation with the show runner about what the viewer would be looking at and what was important to talk about. This shot was more technical and took quite a while to shoot, each take was a more condensed and streamlined version getting to the essence of what needed to be conveyed. It was very interesting. After the initial shot at the work table, various B roll shots were taken for close ups of the work. Care had to be taken to make sure there was continuity with the overall shots previously taken. Questions were posed by the show runner, like “weren’t you holding that with your other hand in the other shot?” As a viewer, you don’t often think about these issues – if the show is done well (obviously, This Old House is).

Once they left the work table shot, they prepared to shoot in the living room where the coffers were to be laid out, so the group was allowed to go downstairs and watch the shot in person. Tommy and Jeff used a layout stick to mark the floor of the room and those marks would later be transferred to the ceiling using a laser. This part was really cool because we could see not only the “shot” but all that goes into the shot. You can see show runner John Tomlin talk to the hosts and ask them to redo a part of the scene, or the camera operator crouched on his knees or how the “extras” walk through the shot the same way every take. Up until this point, the only regular cast members we had the chance to see were Kevin, Tommy and Jeff – and that was all we were expecting to see. But during the end of the shooting for the morning, I turned my head and was surprised to find I was standing right next to Richard! He saw me do a double take and smiled, and after I pointed at my camera and then at him, he nodded with a sly grin.

After shooting, Richard took us outside to talk about how special the septic system here was. As exciting as that subject seems, I really don’t remember what he said about it, but he actually became my favorite story teller of the cast. He genuinely seemed like he wanted to talk to 30 strange fans and even answer one guy’s oddly specific and detailed sewer questions. He talked about how his sons came to decide to work with him in the business, how he took over for his own father in the speaking roll on season one of This Old House 40 years ago after his father got tongue tied and passed those duties on to him in his early 20’s, and finally about how Tommy pranked Kevin the very first time they met by nailing his tool box down to the ground. I left there thinking about applying for a job at his shop! While we were outside, I caught a glimpse of Mark, the masonry expert.

After we talked about sewage for a good long time, we were ready for the barbecue that was part of the contest winnings. They set up tables on the deck and through the house, luckily the weather changed and it was sunny and delightful outside. There was a big buffet of really tasty food. While in line we chatted with a really nice couple who was very close to our age and got tips on where to go on our planned vacation to Rhode Island a month later. we got the skinny on which Newport mansions to see, where the best beaches were – what luck!

We ended up sitting down to eat at a table with Jeff Sweenor, the builder they recently collaborated on with the Net Zero house season, and were working with him again. Chit chat included a discussion of the special wood trim being used, called Solid Select. It is an exterior grade trim that comes from New Zealand that is treated for outdoor use and comes pre-primed. It is so straight and defect free, they not only used it for exterior trim, but used it throughout the interiors as well. Sadly, no one carries it outside New England – yet.

After we finished eating and wiped all the barbecue sauce off our hands, I got all the cast that was there (pretty much everyone but Norm and Roger) to sign my copy of the recent This Old House book. I don’t care if that makes me look like a dorky fan-boy, when else would I get a chance like that? After that, the crew in charge of the Insider contest winners coordinated a lot of photo opportunities which made their way into a very nice article on the day here: TOH Westerly

Jim Mehaffey, AIA, Senior Project Manager

I am an architect with 20-plus years experience in the health care and senior living sector. I am an enthusiastic pragmatist and fan of sarcasm.

My First Job Interview

April 2, 2019

This is the 46th topic in the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is “My First Job Interview” . A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

–>Eric T. Faulkner – Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

Interview — Nervous Energy

–>Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

“my first interview”

–>Brian Paletz – The Emerging Architect (@bpaletz)

My First Interview – Again

–>Mark Stephens – Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

My first interview

–>Ben Norkin – Hyperfine Architecture (-)

My First Interview – Your Next Interview

–>Larry Lucas – Lucas Sustainable, PLLC (@LarryLucasArch)

My First Interview That Reconnected Me to the Past

–>Anne Lebo – The Treehouse (@anneaganlebo)

My First Interview