News

Philadelphia Chapter ICAA – Lancaster Walking Tour

October 2, 2020This ICAA, Philadelphia Chapter, member event, begins at the historic Franklin & Marshall College campus and includes a six-block walk to center city along mansion row. See multiple examples of Chateauesque, Tudor Revival, Colonial Revival, English Country, Spanish Revival, Dutch Colonial, Norman Gothic, Queen Anne and Second Empire. Ending in center city, Penn Square supports an additional fourteen architectural styles within a two-block radius of the 1874 Gothic Revival Civil War memorial. The vast inventory of diverse architectural styles in excellent condition impresses even the most fervent architectural critics. Our tour will adjourn with lunch (not included) at the internationally acclaimed 1889 Romanesque Revival Central Market, a commission won by James H. Warner when he was only twenty-four years old!

Philadelphia Architects – Lancaster Work

J.P. McCaskey High School Design Invokes Art Deco Style of the 1930s

September 20, 2019This is the sixth article in a series focusing on Henry Y. Shaub, an architect who had a lasting impact on Lancaster County.

J.P. McCaskey High School is a product of the 1935 Works Progress Administration (WPA) initiative, designed to put Americans back to work following the Great Depression. The building stands tall as a timeless testimony to the creativity and great work by the Lancaster community during difficult times in our country’s history. By 1936, 49-year-old architect Henry Y. Shaub had earned a statewide reputation as a leader in progressive public school design for children of all ages. When retained by the Lancaster City School District to author the city’s first gender integrated school, he took that opportunity to elevate educational design innovation to the next level.

J.P. McCaskey High School is a product of the 1935 Works Progress Administration (WPA) initiative, designed to put Americans back to work following the Great Depression. The building stands tall as a timeless testimony to the creativity and great work by the Lancaster community during difficult times in our country’s history. By 1936, 49-year-old architect Henry Y. Shaub had earned a statewide reputation as a leader in progressive public school design for children of all ages. When retained by the Lancaster City School District to author the city’s first gender integrated school, he took that opportunity to elevate educational design innovation to the next level.

The building, designed in the popular Art Deco style, presents a red brick and limestone façade along Franklin Street. The 540-foot long façade is pierced by a tower that is 97 feet high. The grand lobby is behind the three masonry portals that stand two stories tall. This memorable lobby space features in-laid terrazzo flooring, gilded ceilings, red marble walls and walnut paneling. The auditorium was the largest of its kind in the city with a seating capacity of 1,900. The stage, measuring 83 feet wide and 18 feet high, was also the biggest school stage in the state with the largest “trip curtain” in the country. The stage featured a regulation sized basketball court offering every seat in the auditorium optimal views of the event!

Shaub was most proud of the unique programming elements that he was able to incorporate into the design. This included fully staged home economic apartment, a full sized “teaching” retail display window, a 200-seat library, a 1,000-seat cafeteria, a 200-seat concert hall, art gallery, museum, complete medical unit and a 12,700 square foot multi-functional gymnasium. In his own description of the design, Shaub speaks to the abundant natural light that permeates each classroom and the use of “light green paint for eye conservation.” The exterior materials and details reflect the Art Deco movement of the 1930s including glass block, stylized pressed metal panels, cast stone medallions and cast iron newel posts and railings.

Shaub was most proud of the unique programming elements that he was able to incorporate into the design. This included fully staged home economic apartment, a full sized “teaching” retail display window, a 200-seat library, a 1,000-seat cafeteria, a 200-seat concert hall, art gallery, museum, complete medical unit and a 12,700 square foot multi-functional gymnasium. In his own description of the design, Shaub speaks to the abundant natural light that permeates each classroom and the use of “light green paint for eye conservation.” The exterior materials and details reflect the Art Deco movement of the 1930s including glass block, stylized pressed metal panels, cast stone medallions and cast iron newel posts and railings.

On February 6, 1938, the Lancaster Sunday News reported that more than 8,680 Lancastrians had inspected the city’s “newest palace of education” and offered rave reviews including reactions like “marvelous,” “amazing” and “the most complete school they had ever seen.” John Piersol McCaskey was Lancaster’s beloved educator, mayor and politician. He passed away at the age of 97, just three years before his name was carved in stone over the main entrance to the new school—a palace of education.

Design Intervention is written by Gregory J. Scott, FAIA, Partner Emeritus

For LNP subscribers, here is the link to the original News Article, Architect’s Design for McCaskey High School Invokes Art Deco Style

In the 1950s, Architect Henry Y. Shaub Introduced Mid-Century Modern to Lancaster

August 21, 2019This is the fourth article in a series focusing on Henry Y. Shaub, an architect who had a lasting impact on Lancaster County.

Architects by nature are innovators as well as problem solvers. Google CEO Eric Schmidt said “…innovators don’t just listen to what people tell them; they actually invent something new, something you didn’t know you needed, but the moment you see it, you say, “I must have it.”

In 1952, architect Henry Y. Shaub sat down with funeral home directors Mr. and Mrs. Robert F. Groff, Sr. and presented two very different design concepts for their proposed new funeral home on West Orange Street. According to their son, Robert F. Groff, Jr., “. . . Mom and Dad were handling half of all the funerals in the city and needed to expand their facilities.” Although funeral home designs were not Shaub’s forte, he took this opportunity to think creatively and help the Groffs reinvent the aesthetic for a building of this type.

Good architects typically present their clients with several options to choose from, with the hope that one will resonate and lead to further refinement. Historically, funeral homes or parlors in the city of Lancaster were housed in either repurposed mansions or in new structures designed in a conservative architectural style such as Colonial Revival. Shaub presented the Groffs with two very different options.

The first was a predictable and attractive three-story, three bay, red brick neo-colonial concept with a one-story annex including an overhead garage door to screen visitor parking from public view. The second concept was an entirely different look for a funeral home and featured a style foreign to the city of Lancaster—mid-century modern. Characterized by a clean aesthetic with an emphasis on rectangular forms, horizontal lines and an absence of decoration, this second concept, which the Groffs selected, turned heads in a city steeped in traditional architecture!

Groff, Jr. recalls that his parents said to Shaub: “. . . make it look like a marble monument and give the funeral home a new look!” The result was a building that stood out in sharp contrast to the surrounding neighborhood and remains one of the few genuine examples of mid-century modern architecture in downtown Lancaster today.

Design Intervention is written by Gregory J. Scott, FAIA, Partner Emeritus

For LNP subscribers, here is the link to the original LNP Article, “In the 1950s, architect Henry Y. Shaub introduced a new style to the city.”

A New City School Brought Spanish Revival Flair to 1920s Lancaster

July 24, 2019This is the fourth article in a series focusing on Henry Y. Shaub, an architect who had a lasting impact on Lancaster County.

The world expositions of the 19th and 20th centuries often led to new architectural styles in the United States. The Panama-California Exposition of 1915 was no exception. San Diego hosted a two-year long celebration for the opening of the Panama Canal. The architects who designed the structures for this grand event deviated from the Greek and Roman architecture traditionally used for these types of exhibitions and instead selected Spanish Revival for the theme. This unique style featuring red tile roofs, walls of stucco, decorative wrought iron and half-round arches, doors and windows captured the attention and imagination of visitors everywhere, including those from the east coast.

The world expositions of the 19th and 20th centuries often led to new architectural styles in the United States. The Panama-California Exposition of 1915 was no exception. San Diego hosted a two-year long celebration for the opening of the Panama Canal. The architects who designed the structures for this grand event deviated from the Greek and Roman architecture traditionally used for these types of exhibitions and instead selected Spanish Revival for the theme. This unique style featuring red tile roofs, walls of stucco, decorative wrought iron and half-round arches, doors and windows captured the attention and imagination of visitors everywhere, including those from the east coast.

Local entrepreneur Milton S. Hershey and architects C. Emlen Urban and Henry Y. Shaub were captivated by the charm and character of this non-indigenous architectural style and quickly introduced it into their domestic and public buildings when possible. Considered informal, eclectic, fanciful and romantic, the Spanish Revival style remained popular from 1915 to 1940.

By the 1920s, Shaub was emerging as the “go-to” architect in Lancaster County for school design work. In 1923, the school directors of Lancaster City retained Shaub to design what was to be the largest and best equipped elementary school in the city: The George Ross Elementary School. The new school building included 21 classrooms, an auditorium and gymnasium.

The architectural features Shaub selected include low profile hip roofs with red clay barrel tiles, large half round arched windows and door openings, decorative wrought iron grills, cast stone decorative motifs including open textbooks, deep-bracketed overhangs and blind niche balconies. In lieu of traditional stucco on the walls, Shaub elected to use a buff colored wire-cut brick to create the visual texture found in stucco. Today, 95 years later, George Ross continues to serve the needs of elementary school students in a setting and a building design that has withstood the test of time and style despite its Southern California heritage.

Design Intervention is written by Gregory J. Scott, FAIA, Partner Emeritus

For LNP subscribers, here is the link to the original LNP Article, A New City School Brought Spanish Revival Design to Lancaster in the 1920s.

Architect highlighted family business with an Art Deco facade

July 1, 2019This is the third article in a series focusing on Henry Y. Shaub, an architect who had a lasting impact on Lancaster County.

There remains an unwritten rule in the world of architects: Never work for family! However, there are always exceptions to every rule and Lancaster architect Henry Y. Shaub broke that rule in 1929 when he agreed to design a new façade and interior for his younger brother’s burgeoning shoe business on North Queen Street. Henry and Benjamin’s father, John Shaub, started the shoe business in 1880 and the family maintained it as a Lancaster city landmark until it closed in the summer of 2012.

There remains an unwritten rule in the world of architects: Never work for family! However, there are always exceptions to every rule and Lancaster architect Henry Y. Shaub broke that rule in 1929 when he agreed to design a new façade and interior for his younger brother’s burgeoning shoe business on North Queen Street. Henry and Benjamin’s father, John Shaub, started the shoe business in 1880 and the family maintained it as a Lancaster city landmark until it closed in the summer of 2012.

Part of the store’s stature on Queen Street derived from its unique and unusual style of architecture, especially for Lancaster County, Art Deco. A style born after the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922, and further advanced at the Paris international exhibition Arts Decoratifs in 1925, Art Deco represented luxury, glamour, exuberance and most of all modernity. Art Deco influenced fashion, industrial design, movie theaters, trains, cruise ships, automobiles, jewelry, and even had its own lettering style. From all accounts, the Art Deco style we see on the building today replaced an earlier Queen Anne façade and interior.

Shaub’s expertise included many different architectural styles, but Art Deco was one of his favorites, evidenced by the number of significant commissions where he used it, and McCaskey High School is the largest and most prominent. Some of the notable Art Deco features on the three-story Shaub’s Shoe Store include the large plate glass window above street level flanked by green translucent panels, each with a center-pivot lozenge window, and the one story tall brass lantern mounted above the side entry.

Additionally, the cast bronze stylized peacocks and zig zag design above the second floor window, the flat relief carvings in the travertine-like stone facing, and finally the signature Art Deco lettering featuring high-waisted center strokes on certain characters all combine to make this an Art Deco façade.

Additionally, the cast bronze stylized peacocks and zig zag design above the second floor window, the flat relief carvings in the travertine-like stone facing, and finally the signature Art Deco lettering featuring high-waisted center strokes on certain characters all combine to make this an Art Deco façade.

The rear of the building offers a curved brick wall with rusticated coursing, glass block infill and a metal decorative logo ornament above the window. The second floor interior features a graceful and organic iron stair rail leading to the third floor and the prominent and impressive floor to ceiling plate glass window mentioned earlier, with its view down to Queen Street.

Design Intervention is written by Gregory J. Scott, FAIA, Partner Emeritus

For LNP subscribers, here is the link to the original LNP Article, Architect Highlighted Family Business with an Art Deco Facade

1915 YWCA gave Lancaster architect Shaub his career-boosting opportunity

May 19, 2019This is the second in a series focusing on Henry Y. Shaub, an architect who had a lasting impact on Lancaster County.

All architects wait for the “big one,” the opportunity to showcase their talent and accelerate their careers. For another notable Lancaster architect, C. Emlen Urban, it was the Southern Market in 1888 at the age of 25; for Henry Y. Shaub, it was the YWCA in 1915 at the age of 28. Both commissions were sizable, highly visible and subject to public scrutiny. Not surprisingly, both of these talented architects came out on top.

All architects wait for the “big one,” the opportunity to showcase their talent and accelerate their careers. For another notable Lancaster architect, C. Emlen Urban, it was the Southern Market in 1888 at the age of 25; for Henry Y. Shaub, it was the YWCA in 1915 at the age of 28. Both commissions were sizable, highly visible and subject to public scrutiny. Not surprisingly, both of these talented architects came out on top.

Urban took advantage of his family connections to the Southern Market Building Selection Committee to help secure his first breakout commission. Shaub, on the other hand, had to employ another tactic to secure his noteworthy and highly sought-after commission. His strategy was collaborating with an out-of-town expert for a design competition. Shaub invited an experienced and accomplished Pittsburgh architect, Harry S. Estep, to join him in submitting a design for the Lancaster YWCA, only the fourth freestanding facility of its kind in the United States. This nationally advertised competition drew interest from east coast and mid-western architectural firms.

The proposed location for the YWCA required a solution that would complement the architecture of the surrounding residential neighborhood, and that would be pleasant to look at from its two primary exposures: North Lime Street and East Orange Street. The Shaub/Estep team chose a style rooted in American tradition and history—Colonial Revival. The 1876 Centennial International Exhibition, held in Philadelphia, had sparked renewed interest in our country’s past architectural heritage. This renewed interest and the resulting Colonial Revival architecture would remain highly popular for another 80 years.

With broad porches, impressive front doors, gabled roofs, fluted Tuscan columns, elaborate dormers, double-hung windows with keystones, Flemish bond brick, fanlights, mutules, quoins and cast stone balustrades, this three and a half story structure provided a familiar appearance and a welcoming presence on a busy street corner. The interior architecture offered a well-designed and well-appointed Colonial Revival experience, including a grand entrance hall and staircase, stained hardwood floors, paneled walls and an impressive auditorium with stage to accommodate several hundred guests.

With broad porches, impressive front doors, gabled roofs, fluted Tuscan columns, elaborate dormers, double-hung windows with keystones, Flemish bond brick, fanlights, mutules, quoins and cast stone balustrades, this three and a half story structure provided a familiar appearance and a welcoming presence on a busy street corner. The interior architecture offered a well-designed and well-appointed Colonial Revival experience, including a grand entrance hall and staircase, stained hardwood floors, paneled walls and an impressive auditorium with stage to accommodate several hundred guests.

The success of Shaub’s first major commission set the stage for a long and successful career that would span 58 years and include hundreds of commissions in dozens of building types and design styles.

Design Intervention is written by Gregory J. Scott, FAIA, Partner Emeritus

For LNP subscribers, here is the link to the original LNP Article, 1915 YWCA gave Lancaster architect Shaub his career-boosting opportunity.

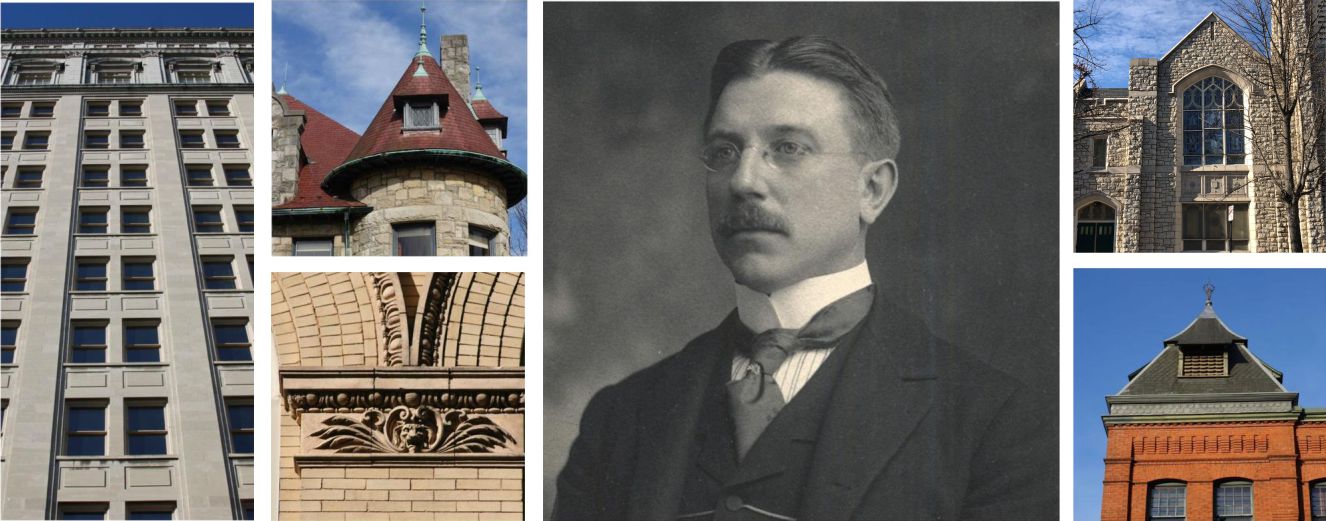

Take a Closer Look at Henry Shaub: An Architect Who Helped Build Lancaster’s “Look”

April 12, 2019Following our multi-part series on architect C. Emlen Urban, this is the first in a series that will focus on another architect whose talents had a lasting impact on Lancaster County.

Although his portfolio of local work was varied and his list of clients impressive, Henry Y. Shaub’s real fame as an architect was what he was able to accomplish in the classroom. This Lancaster native was acknowledged throughout the eastern United States as the leading authority on school design. He would sit among the students to understand how the physical environment, including natural light, acoustics and special relationships, could affect their ability to learn.

Although his portfolio of local work was varied and his list of clients impressive, Henry Y. Shaub’s real fame as an architect was what he was able to accomplish in the classroom. This Lancaster native was acknowledged throughout the eastern United States as the leading authority on school design. He would sit among the students to understand how the physical environment, including natural light, acoustics and special relationships, could affect their ability to learn.

A rising star in his own right, this young architect was often overshadowed, but not intimidated, by his 24-year-older contemporary C. Emlen Urban. At 25, Shaub struck out on his own and promptly entered and won a nationwide competition to design the highly sought-after Lancaster YWCA commission in 1915.

Little has been written about this noteworthy architect who followed in the footsteps of Urban. He not only continued to reshape the architectural landscape of our community, but also to shape the minds of our children through designing better environments for learning.

This series will focus on the diversified work of architect Shaub including the Lancaster YWCA (c. 1915); Posey Iron Works (c. 1918); Shaub Shoe Store (c. 1929); Manheim Township’s Brecht Elementary School (c. 1929); J.P. McCaskey High School in School District of Lancaster (c. 1936); and Groff Funeral Home (c. 1950) — just to name a few.

Shaub’s innovation and bold design ideas earned him an honor that only 3% of all architects achieve: being named a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects. The fellowship distinction is reserved for architects who have made outstanding contributions to the profession.

SHAUB BIOGRAPHY

SHAUB BIOGRAPHY

Born Oct. 13, 1887, Henry Y. Shaub was educated at Bordentown Military Institute and Franklin & Marshall Academy, then received an architectural degree from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1909.

In 1912, he married Bertha Barron, an orphan who had been raised at the Northern Home for Friendless Children in Philadelphia. They would continue living with his parents, at 246 E. Orange St., for a decade.

Records indicate Shaub registered for both World War I and World War II, but he would never serve in the military due to being described as “crippled from infantile”.

For the full article and photos, subscribers can access the LNP on-line edition of Take a Closer Look at An Architect Who Helped Build Lancaster’s “Look.”

Tying up the life of a legend: architect C. Emlen Urban

March 17, 2019C. Emlen Urban Series – Final Installment

Cassius Emlen Urban’s 53-year career was nothing short of extraordinary and his contributions were immeasurable. He singlehandedly introduced Lancastrians to a new vocabulary of bold and sometimes uncomfortable architectural styles. Prior to Urban’s arrival in 1884, red and brown tones comprised the downtown Lancaster color palette and the architectural styles were predominately Queen Anne, Georgian and Federal. This quickly changed in 1892 when Watt & Shand debuted Urban’s French Beaux Arts style department store in the heart of Penn Square. One by one, other city merchants retained Urban to help them advance their own images.

Cassius Emlen Urban’s 53-year career was nothing short of extraordinary and his contributions were immeasurable. He singlehandedly introduced Lancastrians to a new vocabulary of bold and sometimes uncomfortable architectural styles. Prior to Urban’s arrival in 1884, red and brown tones comprised the downtown Lancaster color palette and the architectural styles were predominately Queen Anne, Georgian and Federal. This quickly changed in 1892 when Watt & Shand debuted Urban’s French Beaux Arts style department store in the heart of Penn Square. One by one, other city merchants retained Urban to help them advance their own images.

The next 30 years saw a dramatic transformation in the scale and texture of the downtown landscape including French Baroque, Italian Renaissance, Perpendicular Gothic, French Renaissance, and fresh interpretations of Romanesque and Greek Revival. But what do we really know about the architect behind the pen? How did he do it? What made him tick? Did he ever sleep while designing more than 273 buildings?

We do know that Urban was the second child born to Conestoga residents Amos and Barbara Anne Urban on February 20, 1863. His formal education ended after graduating as the valedictorian of his high school class, followed by a four-year apprenticeship with two unique and well-established, but completely different architects in Scranton and Philadelphia. Shortly after starting his private practice in 1884 at the age of 21, Urban married Jennie Olivia McMichael in her parents’ home at 28 East Lemon Street. He was 23 and Jennie was 24. The couple moved to 141 East New Street to begin their life together and raise their two children: Miriam and Rathfon. Rathfon and Urban’s younger brother Christopher Urban, and nephew Frank Urban were employed by Urban over the course of five office relocations in center city. Beyond these gentlemen and his head draftsman, Ross Singleton, little is known about his office personnel.

What Urban lacked in physical stature at only five feet, six inches tall, he more than made up for in his larger than life personality and engaging blue eyes. His social and business connections in the community were second to none, holding court with notable local figures including Milton S. Hershey, Peter Watt, James Shand, Herman Wohlsen, Christian Guzenhauser and Congressman William W. Greist. Research to date has come up short on a significant number of portrait or family photos, with a grand total of five found so far. We do know he traveled extensively to Europe, South America and the Mediterranean from 1911 through 1934, which were also the most prolific years of his practice. Although his public designs were quite progressive, his style preference for the two residences he designed for himself was the conservative and understated colonial revival.

What Urban lacked in physical stature at only five feet, six inches tall, he more than made up for in his larger than life personality and engaging blue eyes. His social and business connections in the community were second to none, holding court with notable local figures including Milton S. Hershey, Peter Watt, James Shand, Herman Wohlsen, Christian Guzenhauser and Congressman William W. Greist. Research to date has come up short on a significant number of portrait or family photos, with a grand total of five found so far. We do know he traveled extensively to Europe, South America and the Mediterranean from 1911 through 1934, which were also the most prolific years of his practice. Although his public designs were quite progressive, his style preference for the two residences he designed for himself was the conservative and understated colonial revival.

Under the heading of trivia: on November 16, 1911, the Lititz Record reported that Urban, an “excellent fisherman”, landed the largest bass ever recorded in the Susquehanna River at Peach Bottom. Weighing 6.25 pounds “he lifted the fish with pole and reel and fed a multitude of Urbans.” Unrelated, the October 6, 1934 edition of the Gettysburg Times reported that his Buchanan Avenue home was burglarized by a 21-year-old suspect from Atlanta, Georgia! And lastly, to his grandchildren, he was known as Baba!

His final commission was documented March 15, 1939 for East Orange Street resident John S. Groff, almost 80 years ago to the day of this article. Urban passed away two months later on May 21, 1939 at the age of 76 and is buried at the Greenwood Cemetery in Lancaster, along with his immediate family. The understated granite headstone simply says – URBAN with the incised biblical verse: “UNTIL THE DAY BREAK AND THE SHADOWS FLEE AWAY.”

Author’s Note: It has been an honor to share C Emlen Urban’s story with you these past two years. A special thank you to his great granddaughters, Miriam and Alexa, for their insightful contributions and Deb Oesch and Alex Kiehl for their incredible discoveries and research assistance.

For this month’s full article and photos: Tying up the life of a legend: architect C. Emlen Urban and links to previous articles in the series, visit LNP On-line.

First Time Was The Charm for Urban’s “One-Off” Designs

February 19, 2019C. Emlen Urban Series – CONTINUED

With more than 24 months of research completed, there is sufficient evidence to claim that C. Emlen Urban designed at least 39 different building types that encompassed 25 architectural styles!

Essentially, Urban spoke 25 languages and possessed enough knowledge to understand the design components, nuances and requirements for nearly 40 different categories of buildings, ranging from a single-story residence to a 14-story skyscraper and everything in-between!

As prolific as Urban was in producing over 273 designs during his career, there are a fair number of “one-off” commissions in his portfolio–defined as building types or design styles that he only designed once. Some were quite glamorous, while others were rather mundane. The following are a few of Urban’s one-offs: a bakery, funeral home, community center, hospital, children’s home, freestanding farmers market, movie theater, YMCA, drug store, tobacco shop, insane asylum, opera house interior, tavern, Moose Lodge, home for the aged, a storybook style cottage, a church crown and storage garages. All are worthy of mention and a few certainly deserve additional explanation.

As prolific as Urban was in producing over 273 designs during his career, there are a fair number of “one-off” commissions in his portfolio–defined as building types or design styles that he only designed once. Some were quite glamorous, while others were rather mundane. The following are a few of Urban’s one-offs: a bakery, funeral home, community center, hospital, children’s home, freestanding farmers market, movie theater, YMCA, drug store, tobacco shop, insane asylum, opera house interior, tavern, Moose Lodge, home for the aged, a storybook style cottage, a church crown and storage garages. All are worthy of mention and a few certainly deserve additional explanation.

In April of 1898, Urban and other representatives from Lancaster County were directed to tour and inspect insane asylums around Pennsylvania to gain knowledge prior to beginning the design and construction of a new state of the art facility for Lancaster. The end result was an attractive three story red brick structure designed to support the latest concepts in the moral treatment’ of patients with a special focus on the psychological and emotional state of the individual. Beyond design concepts, Urban introduced the latest building technologies including refrigeration, production kitchens and mechanical systems. The structure remained in use for 70 years.

The five story Lancaster YMCA was constructed at the corner of North Queen and West Orange Streets in 1900. Urban was just 37 years old when he designed this monumental Beaux Arts building complete with an indoor pool. He only designed this one YMCA in his career.

The five story Lancaster YMCA was constructed at the corner of North Queen and West Orange Streets in 1900. Urban was just 37 years old when he designed this monumental Beaux Arts building complete with an indoor pool. He only designed this one YMCA in his career.

Interestingly, the building type that launched his career in 1888 was a ‘one-off’ design. The free-standing Queen Anne style Southern Market was heralded as ‘one of the grandest in size and appearance’ in the city. The 873 seat Grand Theatre, located at 135 N Queen Street, offered movies to audiences from 1913 through the 1960s. This one-off design by Urban was considered a showpiece for movie goers.

For any architect, designing a hospital requires a great deal of knowledge, trust and communication with the stakeholders. The 1902 three story Georgian Revival Lancaster General Hospital designed by then 39-year-old Urban was his sole free standing medical hospital.

All architects fall on hard times sometime during their careers. Perhaps 1919 was a slow year for Mr. Urban when he agreed to design a row of one story garages on the 300 block of N Queen Street. These simple red brick structures survive today and now house the retail shops of Building Character one hundred years after they were built!

All architects fall on hard times sometime during their careers. Perhaps 1919 was a slow year for Mr. Urban when he agreed to design a row of one story garages on the 300 block of N Queen Street. These simple red brick structures survive today and now house the retail shops of Building Character one hundred years after they were built!

Can anyone deny that Urban was clearly a ‘one of a kind’ architect himself?

Gregg Scott, FAIA

The LNP published version of this article is available to subscribers on-line: The First Time was the Charm

Historical Photo Credits: LancasterHistory.org, Hershey Archives and LGH Archives

Urban’s Griest Building Boosted Lancaster PA into the Skyscraper Age

November 14, 2018C. Emlen Urban Series – Part 20

On January 19, 1914, Milton S. Hershey wrote an unsolicited letter of reference to U.S. House of Representative William Walton Griest espousing the merits and talents of Lancaster’s young architect C. Emlen Urban. Hershey concluded the endorsement by stating, “We have a great deal of confidence in his ability as an architect and can safely recommend him as being very capable and very honorable in his line of work.” Ten years later, Lancaster City would see its first skyscraper rise 14 stories above Penn Square. It would retain its distinction as the tallest building in Lancaster for 80 years.

On January 19, 1914, Milton S. Hershey wrote an unsolicited letter of reference to U.S. House of Representative William Walton Griest espousing the merits and talents of Lancaster’s young architect C. Emlen Urban. Hershey concluded the endorsement by stating, “We have a great deal of confidence in his ability as an architect and can safely recommend him as being very capable and very honorable in his line of work.” Ten years later, Lancaster City would see its first skyscraper rise 14 stories above Penn Square. It would retain its distinction as the tallest building in Lancaster for 80 years.

Supporting the claim that relationships build buildings, Hershey, Griest and Urban were mutual friends and business acquaintances for decades, sharing common ground through social clubs, education and politics. Griest was president of three Lancaster public utility companies: Conestoga Traction Company, Edison Electric Company and the Lancaster Gas Light and Fuel Company. The boards of directors commissioned Urban to design a signature structure to honor Griest and house their expanding businesses.

Urban chose two of the most popular styles of the time, French Beaux Arts and Italian Renaissance Revival, to define this landmark skyscraper. The structural steel frame permitted fast construction and had an immediate impact on the city skyline. At street level, pedestrians enjoy Urban’s gift for humanizing large buildings through his use of graceful arches, decorative stone panels with shields, festoons, urns, pilasters and even stone rope. The 12th, 13th and 14th floors comprising the building’s crown included a 300-seat auditorium and ballroom with a green and gold frescoed ceiling. The exterior of the crown is a well-proportioned and beautifully detailed example of Italian Renaissance architecture with glazed terra cotta arched pediments, dentils, curved brackets, balustrades and even a lion’s head cornice.

The Griest Building’s acceptance was so profound and so fast that it quickly stole the thunder from the ever popular Woolworth Building, leading to its eventual demise. On September 21, 1925, The New Era reported that “Time may bring other skyscrapers to Lancaster, but the Griest Building will never forfeit its claim to priority.”

The full article C. Emlen Urban’s Griest Building Boosted Lancaster in the Skyscraper Age is available on LNP News.